Review: Backscatter Airlock vacuum integrity check system

Vacuum housing integrity check systems

Vacuum housing integrity check systems are not a new idea, with Gates releasing their Seal-Check in 2007 and Hugyfot their Hugycheck in 2009. There seems to be a renaissance of interest in them more recently with units now being available from several manufacturers. This in itself has provoked much interesting debate on the Wetpixel forum.

The principle is that the user uses a pump to draw a vacuum into the housing. By then monitoring this vacuum, the housing’s seal integrity can be checked and verified. As an added benefit, the lowering of pressure inside the housing can also help hold ports in place.

There are a number of different ways of both achieving the vacuum and monitoring it. All rely on some form of valve that penetrates through the housing and hence relies on o-rings to seal. To create the vacuum, there are mechanical pumps and electronic pumps and similarly, there are both electronic and analog methods of monitoring it. Typically electronic ones rely on some form of pressure monitoring device that constantly monitors the housing’s internal pressure and gives a visual warning via colored or flashing LEDs if this should change. Analog ones typically use a pressure gauge to monitor the housing pressure within the housing, with a vacuum being created at some point pre-dive and then checked some time thereafter, but still pre-dive. If the pressure is unchanged, this suggests that the housing’s seals are intact.

What do they do?

Despite some proselytizing from some individuals, no vacuum system by itself can guarantee that a housing will not flood. In fact, there have been examples of the units themselves causing floods! The attitude of saying that because a light is flashing, or a unit is holding a pressure, the housing will not let water in is misguided. Avoiding leaks still relies on rigorously following a standard procedure with regard to o-ring maintenance and housing assembly. Once this has been carried out, then a leak check system can verify the effectiveness of the process.

One should also accept that a leak (or camera electronic/mechanical failure) is always possible despite the best procedures. If bringing images home is critical, then a spare body is the only way to guarantee that this will take place. Some years ago, I bent a pin in my camera’s Compact Flash card slot. This meant that the body was effectively useless. Fortunately, I had a spare body and was able to keep shooting!

Another possible issue with the electronic continuous monitoring type systems is that temperature changes affect the internal pressures and can give false results. Although I gather that some of these are temperature compensated, I have had a few occasions when a housing started flashing red lights at me due to this. Setting up the housing in a cold environment and then moving it to a (relatively) warm one can cause this, and I have also heard that with some video systems (RED in particular) that run very hot, are notorious for causing “false positive” results. This may be something that documentary shooters, with that one chance of getting the shot, may want to be aware of. Whilst it is perhaps better to be safe rather than sorry, this can also cause you to miss photo opportunities, from which some people may need to derive income.

Backscatter Airlock

I saw a very early prototype of Backscatter’s Airlock housing vacuum and port lock system at DEMA in 2012. At that time, I asked Backscatter’s Jim Decker if I could carry out an early review once the system came to market. The Airlock is “brand agnostic” with differently sized bulkheads available for most housing brands, including a fitting for the company’s Wahoo video monitor housing.

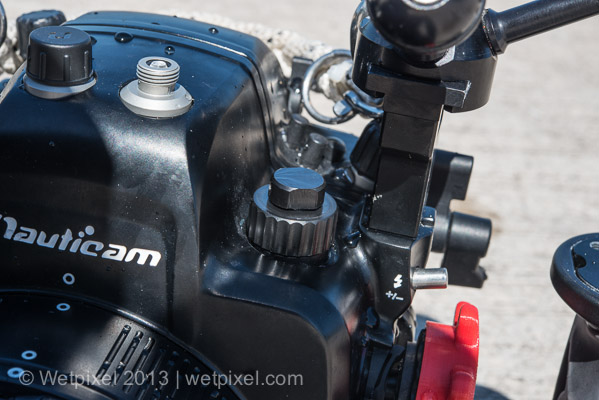

The bulkheads have a sealing cap, which allows the Airlock to be removed and the port to be sealed if required. They simply screw into an available port in the housing, and then the Airlock valve screws into the adapter. The valve assembly is made of aluminum and has a quick disconnect fastener similar to, although a lot smaller, those that most divers are familiar with on their BCD’s low pressure inflator. It is also supplied with a plug attached to it with a cable tether. The valve then attaches to a gauge, which in turn can be attached to a simple hand pump.

The user simply pumps the pressure within the housing down whilst watching the pressure gauge (Backscatter recommend a vacuum of at least -5 in.Hg). The pump can then be detached, and the housing left for between 5 to 15 minutes. After this, the pump and gauge can be re-attached and if the seals in the housing are intact, the pressure reading on the gauge should be constant. Backscatter recommend that the interval between initial de-pressurization and retesting should not exceed 15 minutes due to the potential for temperature and hence pressure changes.

There is no need to release the vacuum before diving, and in fact, if the housing is not equipped with a port lock, the vacuum will help prevent the port from coming loose. In order to open the housing however, it will need to be released, and this can be done by simply refitting the gauge without the pump attached. Once the pressure has reached equilibrium, the housing can be opened as normal.

In use

Backscatter supplied me with an adaptor for the M16 sized port in my housing and I found that the bulkhead installed into my housing with no problems. There have been a few issues reported with the clearances on the adaptors for different housings reported in the forum, but I gather that Backscatter has been pro-active in finding solutions for these. I think that this can in part be avoided by being absolutely clear which housing you will be using it with prior to purchasing the unit. I was able to attach the Airlock within minutes.

The gauge/pump assembly is also simple to attach. The pump is a simple hand pump and interfaces with the gauge unit via a simple friction fit. It is a very simple design and has a number of minor possible issues to be aware of. Firstly, if the user pumps too vigorously, this can “overun” the pump and it ceases to produce a vacuum. The key is to use deliberate slow pumps rather than fast and furious ones! If this makes it sound like it takes a long time to reach sufficient vacuum, it does not. In fact, it is significantly quicker than a battery driven pump that I used with another unit some time ago. Secondly, and this is a similar issue, the pump can quite easily disengage from the fitting holding the gauge. If this occurs, whatever vacuum that is within the housing is lost and the process must be repeated.

Whilst the above sounds a bit negative, the pump assembly is also very light (good for travel), does not require any batteries or power and is very simple. It just needs a little careful handing.

To test the Airlock, I deliberately inserted a pet hair through my housings main o-ring seal. This did result in the housing losing enough vacuum (-3 in.hg) in 15 minutes to “alert” me to the potential leak. If there was to be a similar issue, I am confident that the Airlock would give the user warning and allow them to remedy it. Of course, preventing pet hairs or any other detritus from being in the o-rings on a housing is a fundamental part of a pre-dive inspection routine.

I am also pleased to report that since installing the unit, and having dived a fair amount with it, I have yet to have an “actual” loss of vacuum due to an issue with the housing. For me, this is perhaps where the fundamental value of these systems lies. Leak prevention cannot be attributed to any one factor, although proper care of the housing and its seals will ensure that leaks are very unlikely. During the debate about these systems, someone said that I rely on a quick dunk in the rinse tank to check my housing seals. Whilst I do look for bubbling in the rinse tank, I actually avoid leaks by spending time and attention to the housing’s seals long before I get anywhere near water. For me, vacuum systems do the same duty, in that they provide a verification of the efficacy of my pre-dive preparations.

The Airlock does do a great job of providing this verification. It is light, simple and effective. It can be fitted to many different still and video housings and even moved between different housings if required. Used as discussed above, it should help to avoid the costly results of a housing flood.

The Airlock is available from Backscatter priced at $399. The company has also just released a version of the Airlock with an electronic LED Alert valve that provides for continuous monitoring of the vacuum. This costs $499. It was not tested as a part of this review.

FTC Disclosure

The Airlock was supplied free of charge to the reviewer by Backscatter in return for him product testing some other (non-vacuum) products.