Underwater imagery from the finalists of WPOTY 2017

As reported on Wetpixel earlier, the results of the 2017 Wildlife Photographer of the Year (WPOTY) contest were announced earlier this week. Whilst the winners represent an amazing body of work many of the finalists in each category are stunning. What follows is a showcase of underwater imagery from WPOTY 2017 along with photographer-submitted detailed captions about each picture and how they were captured.

Snap shot

Rodrigo Friscione Wyssmann, Mexico

Behaviour: Amphibians and Reptiles

In the shallows of Mexico’s Chinchorro Bank Biosphere Reserve, two American crocodiles – both about 3 metres (10 feet) long–faced off. Just before the rivals lunged at one another, Rodrigo submerged, holding his breath. Powered by their strong legs and muscular tails, jaws snapping, the crocodiles went for each other’s throat and eyes. Though American crocodiles are territorially aggressive, combat under water is rarely witnessed smaller crocs usually give way to larger ones–and this fight lasted just seconds before the intruder backed down. But lying on the sand with his camera pre‑set to shoot into the surface light, his strobes aimed downwards to minimize backscatter (caused by illuminated particles), Rodrigo captured the clash and got the shot he had dreamed of for years.

Nikon D800 + 16 -35mm f4 lens at 16mm; 1/250 sec at f6.3; ISO 200; Nauticam housing; two Inon strobes.

The look of a whale

Wade Hughes, Australia

Finalist 2017, Animal Portraits

The female humpback whale repeatedly cruised past Wade, each pass slow and measured –once so close that he could have touched her. She was sizing him up to see if he posed any potential risk to her young calf watching him a little way off. Wade was snorkelling off Tonga’s Vavaʻu Islands, a nursery for humpbacks. The females give birth there, and the calves build up their strength and learn to dive, relatively safe from killer whales. Being the subject of her searching, intelligent gaze was, he says, “humbling,” and he knew full well that, despite her great size-some 10 metres (33feet) long–she was surprisingly agile and capable of defending her calf against any perceived threat. This vigilant mother was part of a group that had migrated north from the Antarctic to overwinter in the warm (but food-poor) Pacific waters. They effectively fast here, but the calves, suckling on their mothers’ fat-rich milk, rapidly put on weight. Once the calves are big enough, their mothers lead them on the more than 6,000-kilometre (3,730-mile) journey back south to page 2of 6the Antarctic feeding grounds to feast on krill. “With a close-up portrait, I wanted to capture something of the intensity of her look and her intelligence,” says Wade. Once she had checked him out and had satisfied herself that he was harmless, she allowed her calf to come closer so that it, too, could satisfy its curiosity.

Canon 5D + 24–105mm f4 lens; 1/250 sec at f8; ISO 400; Nauticam underwater housing.

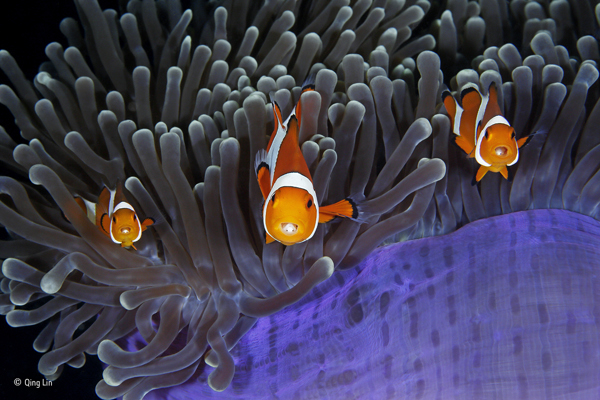

The insiders

Qing Lin, China

Finalist 2017, Under Water

The bulbous tips of the aptly named magnificent anemone’s tentacles contain cells that sting most fish. But the clown anemone fish goes unharmed thanks to mucus secreted over its skin, which tricks the anemone into thinking it is brushing against itself. Both species benefit. The anemone fish gains protection from its predators, which daren’t risk being stung, and it also feeds on parasites and debris among the tentacles; at the same time, it improves water circulation (fanning its fins as it swims), scares away the anemone’s predators and may even lure in prey for it. While diving in theLembeh Strait in North Sulawesi, Indonesia, Qing noticed something strange about this particular cohabiting group. Each anemone fish had an extra pair of eyes inside its mouth–those of a parasitic isopod (a crustacean related to woodlice). An isopod enters a fish as a larva, via its gills, moves to the fish’s mouth and attaches with its legs to the base of the tongue. As the parasite sucks its host’s blood, the tongue withers, leaving the isopod attached in its place, where it may remain for several years. With great patience and a little luck – the fish darted around unpredictably – Qing captured these three rather curious individuals momentarily lined up, eyes front, mouths open and parasites peeping out.

Canon EOS 5D Mark III + 100mm f2.8 lens; 1/200 sec at f25; ISO 320; Sea & Sea housing; two Inon strobes.

Swim gym

Laurent Ballesta, France

Finalist 2017, Behaviour: Mammals

“We were still a few metres from the surface, when I heard the strange noises,” says Laurent. Suspecting Weddell seals – known for their repertoire of at least 34 different underwater call types – he approached slowly. It was early spring in east Antarctica, and a mother was introducing her pup to the icy water. The world’s most southerly breeding mammal, a Weddell seal gives birth on the ice and takes her pup swimming after a week or two. The pair, unbothered by Laurent’s presence, slid effortlessly between the sheets of the frozen labyrinth. Adults are accomplished divers, reaching depths of more than 600 metres (1,970 feet) and submerging for up to 82 minutes. “They looked so at ease, where I felt so inappropriate,” says Laurent. Relying on light through the ice above, he captured the curious gaze of the pup, the arc of its body mirroring that of its watchful mother.

Nikon D4S + 17–35mm f2.8 lens; 1/640 sec at f11; ISO 200; Seacam housing.

Sewage surfer

Justin Hofman, USA

Finalist 2017, The Wildlife Photojournalist Award: Single Image

Seahorses hitch rides on the currents by grabbing floating objects such as seaweed with their delicate prehensile tails. Justin watched with delight as this tiny estuary seahorse ‘almost hopped’ from one bit of bouncing natural debris to the next, bobbing around near the surface on a reef near Sumbawa Island, Indonesia. But as the tide started to come in, the mood changed. The water contained more and more decidedly unnatural objects – mainly bits of plastic – and a film of sewage sludge covered the surface, all sluicing towards the shore. The seahorse let go of a piece of seagrass and seized a long, wispy piece of clear plastic. As a brisk wind at the surface picked up, making conditions bumpier, the seahorse took advantage of something that offered a more stable raft: a waterlogged plastic cotton bud. Not having a macro lens for the shot ended up being fortuitous, both because of the strengthening current and because it meant that Justin decided to frame the whole scene, sewage bits and all. As Justin, the seahorse and the cottonbud spun through the ocean together, waves splashed into Justin’s snorkel. The next day, he fell ill. Indonesia has the world’s highest levels of marine biodiversity but is second only to China as a contributor to marine plastic debris – debris forecast to outweigh fish in the ocean by 2050. On the other hand, Indonesia has pledged to reduce by 70 per cent the amount of waste it discharges into the ocean.

Sony Alpha 7R II + 16–35mm f4 lens; 1/60 sec at f16; ISO 320; Nauticam housing + Zen 230mm Nauticam N120 Superdome; two Sea & Sea strobes with electronic sync.

Circle of life

Jordi Chias Pujol, Spain

Finalist 2017, Underwater

A school of Atlantic horse mackerel bunch up as they are circled by predators, mostly European barracudas (striped) and bluefish. Jordi was looking for dolphins and whales around seamounts off the Azores when he got the tip-off divers nearby had spotted birds gathering above the surface, signposting a swirl of activity beneath. The barracudas are skilful hunters of fish, as are the aggressive bluefish, which often attack shoals as well as hunting other animals such as squid. The baitball was 4-5 metres (13–16 feet) across, constantly moving and changing shape.”It was so dense that I could put my hand inside and catch fish,” says Jordi. By swimming in a tight, coordinated school, the slender mackerel hoped to confuse their attackers, making it difficult for them to pick out individuals. In this case, the strategy seemed to work. Free-diving fora minute or two at a time, Jordi followed them for more than an hour and didn’t see an attack. As the ball slowly managed to move deeper, he captured a top-down perspective of the life-and-death choreography.

Nikon D800 + 16mm f2.8 lens; 1/125 sec at f8 (−1 e/v); ISO 400; Isotta housing; Seacam strobes.

Spawn rivals

David Herasimtschuk, USA

Finalist 2017, Under Water

In the shallows, cloaked in fallen leaves, two large male brook trout size each other up as they attempt to court the female between them. David had been daily scouting the Magalloway River in Maine, USA, for signs of the trout spawning, which they do every autumn in small streams and rivers across New England. Territorial disputes between two or more males are frequent and chaotic–rivals block, bite and ram each other – while the female gets on with digging a nest (aredd) in the gravel, where she will lay her eggs. David often broke through surface ice to lie motionless for hours in the freezing water, allowing the fish to get used to his presence. On a breezy day, tumbling leaves were swept against the bank above one female’s nest. David eventually got close enough to capture the rivalry between her finely patterned suitors, revealing the autumn hues hidden under water. This North American trout, with its distinctive white-edged fins, is in decline, largely due to habitat loss and degradation, but collaborative conservation efforts, which David supports with his images, aim to curb this.

Sony A7RII + 28mm f2 lens + Nauticam WWL-1 lens; 1/60 sec at f7.1; ISO 2000; Nauticam housing; two Inon strobes.

Killer tactics

George Karbus, Czech Republic / Ireland Finalist 2017, Behaviour: Mammals

In the dark Arctic waters of northern Norway killer whales feed on a giant shoal of herring they’ve herded up against the surface into a tightly packed, swirling ball. The whales move fast, and to keep up with the action, George had to be fit. As a free-diver, he was able to react quickly to changing events and angles, holding his breath for up to two minutes, diving down with the whales as many as 300 times a day and observing some special behaviour, including mothers teaching their calves to hunt. On this November day, he was watching a pod of about20 killer whales stunning fish with their tails and swallowing them one by one, when suddenly the whales left the baitball. Regrouping – as if having a tactical meeting - they attacked the herring a minute later with a new strategy, holding their mouths open and flying through the baitball at high speed. ‘It was the most powerful behaviour I have ever witnessed - an intense, life-changing experience.

Nikon D5 + 16mm f2.8 lens; 1/250 sec at f4.5; ISO 5000; Subal housing.

Big sucker, little sucker

Alex Sher, USA

Finalist 2017, Under Water

“The tricky part for the remora, and me,” says Alex, “was staying close enough without being sucked in.” The whale shark, off the coast of the Maldives, was sucking in a huge cloud of krill (shrimp-like crustaceans), while a remora was picking them off from the passing stream. Unlike other species of remoras, this slender sharksucker – up to 1 metre (3 feet) long–often swims freely without a host, but it does associate with larger fish, especially sharks, eating their parasites as well as scavenging their prey. Whale sharks, the world’s largest fish–this one being about 9 metres (29½ feet) long–live on plankton and small fish. Cruising slowly, often near the surface, they suck in water through their remarkably wide mouths and filter out prey as the water passes over their gills. Despite the closure of most commercial whale shark fisheries, this endangered species is still being caught to satisfy the demand for its meat and fins (mainly in Asia) and is also threatened by collisions with ships and entanglement in net fisheries.

Nikon D4 + 16mm f2.8 lens; 1/250 sec at f16; ISO 100; Nauticam housing; Ikelite DS160 strobes