Choose your weapon: SLR versus video cameras for filmmaking

Choose your weapon: SLR versus video cameras for filmmaking

By Jonathan Bird.

It used to be that video had a “look” and cinema had a “look.” You could identify either one pretty well by just looking at the screen. The look of video was characterized by the smoother motion of the higher frame rate (often interlaced fields) and the greater depth of field. Cinema had the “juddery” look of the lower 24 frame/second frame rate as well as the shallower depth of field of 35mm film. (The difference was less pronounced between 16mm film and video due to the smaller size of the film, but the frame rate still made it obvious).

The line has blurred now as film has just about vanished and nearly everything, including Hollywood blockbusters, is shot on “video.” Different types of video cameras have evolved with specific purposes. As a general rule though, most video cameras, even the ubiquitous GoPro, can shoot at any frame rate you like from 24 to 60 and higher, so as a filmmaker you have creative control over the look of the motion in your film. The only thing that is absolutely fixed on any video camera is the size of the sensor. Large sensors and small sensors each create a different look.

What is the “look” of a large sensor? Traditionally, cinema was shot on 35mm film, most popularly with super35 format cameras that run the film vertically through the gate, producing an image on the film that is sized about 24x18mm. This is smaller than the full-frame 36x24mm frame size of a 35mm still camera that runs the film horizontally through the gate. The large image area of the “sensor” (film) creates a “look” which is mostly characterized by the shallow depth-of-field it achieves. Shallow depth-of-field is favored by portrait photographers for making the subject’s face sharp against a soft background, and in cinema it can do the same thing, keeping the background distracting the audience from an actor’s performance in the foreground.

Traditionally, video cameras, even professional models, use sensors considerably smaller than super35 dimensions–between ¼” and 2/3” measured diagonally (6.4-17mm diagonal compared to the 30mm diagonal of super35.) As a result the traditional video camera has significantly more depth-of-field for a given f/stop compared to a film camera. This is not always a bad thing. If you are shooting news, documentary or wildlife where you are tracking things moving quickly, you have a higher chance of producing images that are in focus when you have a little more “wiggle room” in your depth-of-field. Small sensors have a lot of good things going for them in this regard. They also allow lenses to be more compact, they have larger zoom ranges, make par-focal designs less expensive and for underwater use, offer much sharper corners behind dome ports. Smaller sensors have traditionally been used in news and documentary production (such as scores of BBC, Nat Geo and Discovery documentaries) because the cameras offer exceptional image quality while supporting extremely versatile zoom lenses which are needed in the field when there is no time to change lenses. Anyone who scoffs at smaller sensors for motion picture production doesn’t understand it at all. Large and small sensor cameras have their own place and their specific uses. For example, at least 95% of BBC’s Planet Earth and Blue Planet series were shot with small sensor pro video cameras, mostly Panasonic DVCPROHD.

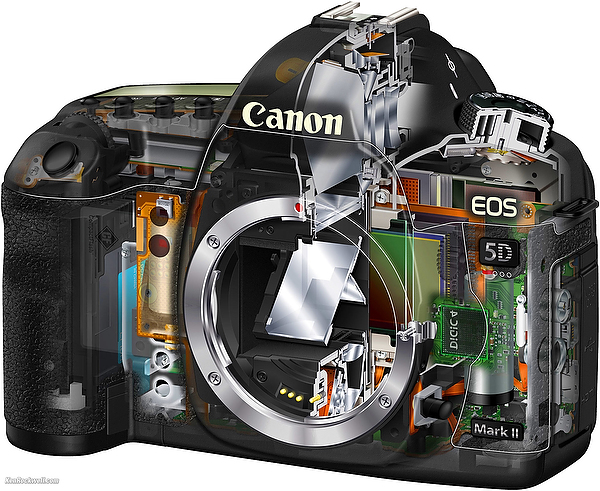

A few years ago, the SLRs came into fashion as a filmmaking tool for one very simple reason: it was an inexpensive way to achieve the look of a large sensor cinema camera.

When the SLRs started producing decent quality video from a large sensor, it was a revelation to low budget cinema; being able to achieve the look of shallow depth-of-field film/digital cinema cameras without the expense of film or a high-end digital cinema camera. However, it came with a few drawbacks:

SLRs typically have lousy audio interfaces, minimal audio controls and substandard audio quality. Audio needs to be handled separately. (Very film-like indeed!) You can work around it, but it’s a pain.

DSLR zoom lenses are not par-focal. That means that the focus plane changes as you zoom them. For example, you zoom in, focus on your subject, zoom out, and now the subject is out of focus. They aren’t cinema lenses. You can work around it, but it’s a pain. Sure you can put a parfocal cinema zoom lens on a DSLR, but if you can afford a cinema lens, you can afford a real cinema camera!

The DSLR has awkward ergonomics for video. Again, you can work around it, but it’s a pain.

SLRs have sensors designed for still photos, with 16+ megapixels. The problem with this is that the processing power required to “downsample” that many pixels into HD video (2 megapixels) or even 4K video (8 megapixels) is simply not there. So the camera manufacturer uses a trick to sample the sensor for video. The technique involves “line skipping” when reading out the pixels from the sensor for each frame of video. This halves the amount of data to be processed, but is equivalent to looking at something through a screen door. It introduces a significant amount of moiré and aliasing artifacts in fine detail that can be quite objectionable. Ironically, this issue has become worse as DSLRs have become “better” with more pixels on the sensor. Earlier DSLRs with fewer pixels actually produced better video than many of the high pixel count cameras available now.

It was worth dealing with these issues when the DSLR was the only game in town and many fantastic movies and television drama programs were shot on DSLR cameras. However, I think it is time to rethink their place:

For several years now there have been numerous reasonably-priced large sensor cinema cameras on the market that address all the shortcomings of the DSLR (audio, ergonomics, aliasing, etc.). There is just no reason to mess around with the DSLR as a filmmaking tool anymore. The Sony NEX FS100 and Panasonic AF100 (for HD) or the Sony FS7 (for 4K) are simply astonishing digital cinema cameras that are available at extremely reasonable prices and have sensors designed for video. They produce incredibly clean, moiré-free shallow depth-of-field images with XLR audio inputs, cinema camera form-factor, true time code, and lens mounts for any lens you want to put on them. With cameras like this available, why on Earth would anyone mess around with DSLR video?

A few words about underwater DSLR video

The semi-pro “advanced amateur” video camera has nearly died in underwater video. Amateurs are now happy to shoot video with a GoPro or the video mode on their point and shoot because it’s small and convenient. Sure, the video is awful, but as they aren’t working for National Geographic, who cares?

Pros have switched to the RED, the Sony F55 or perhaps the PMW-200 or Z100 pro camcorders, depending on what they are shooting. (As I mentioned previously, television production prefers the zoom lenses and all around do-everything functionality of pro camcorders, cinema favors the large-sensor look and RAW workflow of RED and F55). What has happened is that the “advanced amateur” video shooter has become a bit of an endangered species.

This has left divers interested in shooting video above the GoPro level with few choices for cameras or housings. As a result, the camera systems that have stepped in to fill the void are…you guessed it…SLRs and I think you know where I’m going now:

A few reasons DSLRs make even worse underwater video cameras than they do cinema cameras:

- A large sensor on an underwater camera is great for light gathering but extremely hard to get in focus. Depth of field is working against you here. When you see your work on a large monitor, you will be shocked how much of it is totally out of focus.

- A large sensor behind a dome port has terrible corner sharpness unless you are using a fisheye lens.

- One of the greatest gifts of underwater video cameras is the URPRO “flip filter” to selectively add or remove filtration for natural light white balancing. There is no substitute for it. Even the RAW workflow of a RED or F55 will not “fix it in post” except at depths less than about 30 feet. On a DSLR? Forget it. I have yet to see a DSLR housing that offers this feature. Without it I’m sorry, you are not working with a professional tool set. When I shoot with a RED I always have the same dilemma before the dive—do I put the URPRO on the lens or not? Because once the thing is assembled and put in the water I can’t take it off. Oh, how I long for the flip filter!

- Dedicated video cameras have par-focal zooms with macro. You can shoot everything from a nudibranch to a whale shark with the same rig on the same dive. With a DSLR you have to pick a lens with a limited range of usefulness and stick with it the whole dive. Set up for macro? Bummer when that whale shark swims by!

- Image stabilization. Some of the Sony and Canon DSLRs now have image stabilizing lenses that work in video mode, but for the most part, it’s really hard to hold a DSLR housing still enough to shoot professional looking video with one. Dedicated video cameras have had this feature for 20 years and it really helps underwater. Of course many of the larger pro video systems also have a mass advantage. Yes, traveling with a big housing is a huge pain, but shooting with it in the water is a dream because the mass makes it much easier to shoot smoothly. Furthermore, most systems like this are close to neutrally buoyant. DSLR systems are small, shaky and negatively buoyant. Much harder to shoot well. Still, the advanced amateur doesn’t want a 65 pound Pelican case to check for just the housing, so smaller housings are preferable. In this case, the video camera image stabilization really helps get those shots that won’t make the viewer seasick.

Can you get decent underwater video from a DSLR? Sure, sometimes. If you are shooting video where color isn’t that important (or you have some big lights on the rig), there isn’t a lot of fine detail that will suffer from aliasing and moiré, and you get it in focus, it will look fine. But in the vast majority of situations, a video camera in a proper video housing will produce a superior image.

The only argument for a DSLR as an underwater video camera that makes any sense is for the person who is primarily a still photographer who wants to occasionally shoot a little video. Just realize that under most circumstances, the video is not going to look as good as video made by a video camera.

What’s the solution? Yes, they’re an endangered species but there are still a few “advanced amateur” video cameras being made (such as the outstanding Sony AX100). If you really want to shoot decent video, think seriously about a dedicated video camera in a dedicated video housing.

About the author:

Jonathan is an Emmy Award-winning underwater cinematographer and producer, president of the non-profit organization Oceanic Research Group as well as a widely published author, award-winning assignment cinematographer, photographer and speaker. He is the author of 7 books, director of over 20 films and a member of the Wyland Ocean Artist Society.